| Author | Message | ||

| davehouck

Moderator Username: davehouck Post Number: 1336 Registered: 5-2002 |

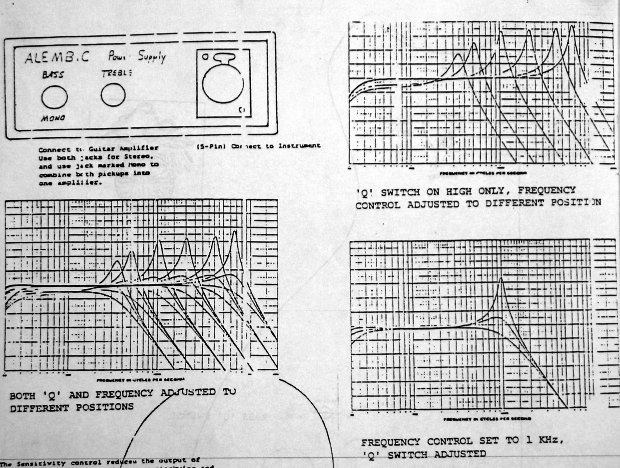

Here is an excellent discussion of the low pass filter from Bob Novy. The original thread is here. A low-pass filter allows frequencies to "pass" (be heard), if they are "low"er than the selected filter frequency. The opposite example is a high-pass filter, which allows higher frequencies to be heard, and elminates those below the filter frequency. On Alembic instruments, the low-pass filter frequency control has a range of 350 Hz to 6 kHz. That means if you leave it "wide open" (6 kHz), you'll basically allow all useful frequencies (for a bass) to pass, and it won't really act as a filter at all. On the other hand, if you set it to the minimum of 350 Hz, then you are starting to filter out some of the highest notes. With standard tuning, the G string on a bass has a fundamental frequency of just under 98 Hz (cycles per second), so let's call it 100 for convenience. Playing an octave higher doubles the frequency, so at the 12th fret on the G the fundamental is 200, and at the 24th fret it's all the way up to 400 Hz - which is below the minimum filter frequency of 350. Now, in addition to the fundamental, you also have to think about the frequencies of the harmonics, or "partials". I won't try to explain all that tonight (where is that book???), but when you pluck an open G at around 100, you also generate tones at various multiples of that, and these overtones have an important influence on how the note sounds to you. So even with much lower notes, setting the low pass filter to minimum is going to make those notes sound less bright, because you start filtering out some of the harmonics. To a certain extent, this is similar to turning down the treble. However, a treble control typically takes effect at some specific frequency, and turning it down lowers everything above that by a fixed amount. A picture would help here, but most tone controls are "shelving", meaning that they have a gradual effect over a small range, and then plateau or flatten out for everything beyond that point. In contrast, a filter will usually roll off progressively, and I believe the standard low pass filters used here decrease at 12 dB per octave. Another way of making that last point is to note that these are not "brick wall" filters: instead of totally eliminating any sound above the filter frequency, the output is gradually reduced, so that one octave higher it will be 12 dB lower, two octaves higher will be 24 dB quieter, and by then you can't really tell anyway. ------ So in at least two ways so far, the low pass filter is different than a typical treble control in that (a) you can specify the frequency at which it takes effect, and (b) it is a little more aggressive in that it continues to reduce higher frequencies by greater amounts. Now we finally get to the Q control. If you've been reading the brochure or whatever, then you've noticed that you may have a 2 or 3 position Q toggle switch, or a "continuously variable Q" (CVQ) knob. They all do the same thing, but with varying flexibility. Draw yourself a picture: a graph in which the x-axis is frequency (using a log scale), and the y-axis is output level in dB (think of it simply as volume). With a simple low pass filter, and no Q applied, you would draw a straight horizontal line from 0 Hz (on the x-axis) to the selected filter frequency, and then draw a diagonal line downward from where the filter kicks in. The output level is rolling off at a continous level above the filter frequency. This is exactly how it would look if you had the Q-switch or knob in the "off" position. But as you increase the Q, then right at the corner where the line (output level) starts to drop down, you would instead see a rather sharp hump - with the output level increasing right at the point of the filter frequency. Someone else might fill in the specific values for the different Q switch and knob options, but the point is that (for example) if you set the filter frequency to 350 Hz and crank up the Q, then for a fairly narrow range (say 330-370) you will see a boost in output, before everything starts to drop off. (I could be off on the numbers here, maybe the peak of the boost is earlier than the filter frequency, I forget. I have an ump-teenth generation xerox of actual measurements from a Series I with various settings of both frequency and Q, but it's too blurred to read the values - which is why the charts haven't been posted here yet). Looking at your drawing again, this peak has both height and width. The height is measured in dB, and in more general audio terms, the width (or perhaps ratio of height to width?) is measured or referred to as "Q", with a tall narrow peak being considered a higher Q, and a more gradual, rolling hill sort of thing being a lower Q. There is some terminology which confuses me here. I'm pretty sure that Q is normally used to characterize the height/width ratio of the peak, but Alembic describes their Q switch positions simply as dB (which would be height). Also, when you start looking at something like the SF-2, you learn that a higher "damping ratio" increases the "resonance", or gives you a higher and sharper peak, but that's more electronics than most of us need to understand (though it is consistent with my understanding of higher Q). There is quite a bit of interesting research, on a variety of acoustic instruments, which suggests that similar resonant peaks (at frequencies specific to particular instruments) are largely responsible for determining the nature of the instrument's sound. This is a pretty complicated subject, but I believe there is some validity to the claim that the filter/Q approach is a more "natural" approach to tailoring sound, than the traditional bass/treble knobs. Whatever. The bottom line is that you can turn down the frequency on the low pass filter to cut out the highs, and then also turn up the Q to give you a fairly dramatic boost right at the point where you've chosen to start rolling things off. It takes a little getting used to, and most people tend to over-do the Q at first, but it turns out to be incredibly flexible. (Message edited by davehouck on March 30, 2008) | ||

| davehouck

Moderator Username: davehouck Post Number: 6384 Registered: 5-2002 |

Bob's contributed another nice post on the subject. The original thread is here. Without meaning to be picky about terminology, I'd like to try to clarify a few things here. First, it really is not appropriate to use the term "shelving" when describing these filters. A shelving filter, or tone control, will raise or lower all frequencies beyond a particular point, by a fixed amount. For example, it might reduce all frequencies above 3 kHz by 10 dB. In contrast, the low pass filter has a roll-off slope beyond the set frequency, such that higher frequencies are reduced at the rate of 12 dB per octave (doubling of frequency). In other words, if the filter frequency is set at 3 kHz, then 6 kHz would be reduced by 12 dB, 12 kHz by 24 dB, and so forth. Second, while these filters may be "parametric" in some literal sense (since you can adjust the frequency and Q parameters), they are really very different animals from what most people would think of when you talk about a parametric equalizer. Here is exactly what you can do with one of these low pass filters and a three position Q switch:  The graph in the lower right shows what the Q switch does. In the high position, it gives you a sharp peak at the set frequency position, while in the off or 0 position it allows the filter to roll off smoothly without a peak, and the middle position gives you a modest emphasis. Note that in all positions of the Q switch, you still end up with a 12 dB roll-off above the set frequency. Q simply determines whether you get an emphasis, and how much, at that frequency. Changing the frequency setting shifts the roll-off point (and the peak, if Q is engaged) right or left, as shown in the upper right. So as you lower the frequency, you are eliminating more of the highs, and more drastically than if you were turning down a shelving treble control. |